This article might be long. And I’ll try not to get too jargon-y, but there might be moments. Sorry in advance. I want to talk about insurance, reinsurance, global climate change, and how these puzzle pieces may interact in a decade or so. Why? Because there’s still time to mitigate risk impacts.

My goals are to keep this article (somewhat) engaging and digestible, share my view on potential risks, and provide a jumping-off point for further reading and research.

(Note: Though I worked as a business journalist and later as a financial regulator to mitigate systemic risk, I’m not an insurance expert by training, so if insurance was or is your focus, I’d love to hear from you and possibly do an interview or ask you to write a guest post. Please reach out!)

Let’s get started already.

Sure thing. When you buy a property, you insure it against risks like fire, damage, theft, and sometimes flood or earthquake, depending on location. To do this, you (the insured) pay a reasonable premium to an insurer. That insurer is betting—based on reams of historical and forecast data—that the likelihood you’ll collect on a payout is low enough for them to turn a profit. And they usually do. That’s why insurance is a viable business.

But there are nuances and less-than-perfect markets. For example, if your house is in a flood zone and you have a US-government-backed mortgage, you must buy flood insurance. Moreover, private lenders can require flood insurance even if the house isn’t in a flood zone. (Cash purchasers can buy or forgo insurance at their discretion.)

But flood and earthquake insurance can be expensive. When I rented an apartment in L.A. in the early 2000s, the earthquake premium was far more expensive than the rest of my renters insurance premium, thanks to the 1994 Northridge earthquake costing insurers too much—so I skipped it. My stuff wasn’t worth much, and I wasn’t on the hook for the apartment building.

If you own a house and you choose to purchase flood or earthquake insurance, you may be able to shoulder expensive premiums to a point—but the more incidents occur in the area, and the more claims are made against the insurance, the higher premiums may rise. If expensive eventually becomes astronomical, then what? People may start to drop coverage, so insurers raise rates more on the remaining insureds, so more people drop coverage if they can, and so on.

That sounds like an insurance death spiral.

Yeah. And this type of vicious spiral does not bode well for insurers, insureds, or governments as climate change spikes rates of wildfires, floods, and other disasters.1

Now, wildfires and hurricanes are events that insurers already routinely handle: each one affects a specific area and can cause devastation that hits insurers hard, but there’s no such thing as a hurricane or wildfire that blankets the entire world. Even so, an increase in event frequency could raise premium costs or drive some insurers to leave the market.

In some areas, that might get tough, like it did in Florida after 1992’s Hurricane Andrew, but back then, the state stepped in and created an entity to insure homes that otherwise couldn’t obtain coverage. (Note: state-backed insurance entities aren’t a full solution; several Florida insurers are currently struggling because their long-time rating agency, Demotech, downgraded them. This situation is an interesting mess, and the linked article is well worth reading.)

As if these types of known problems weren’t enough, new problems loom on the distant horizon.

The word “loom” sounds ominous.

Yes. The most universal risk on the distant horizon involves sea level rise. We know with near-certainty it will occur, but many models put the biggest impacts around or past the year 2100. That can feel easy to ignore, since if losses are far enough in the future, their modeled NPV (net present value) is low. NPV is a valuation method that discounts future cash flows (whether positive or negative) back to the present.

But the risk may be nearer-term than models indicate. Currently, models forecast about a foot of sea-level rise by 2050. But what if long-term effects occur sooner than predicted? This year, in 2022, the UK saw warming that its Met Office had modeled as “plausible” for 2050. Why? One reason is that models may not be capturing all possible feedbacks among different components of climate change. With many complex feedbacks interacting, one effect could spark another, and effects could snowball ever-faster as they pile up.

For example, if the Greenland ice sheet hits a tipping point for melting, decreased glacial surface area could reduce the albedo effect, which determines how much sunlight Earth’s surface reflects back into space. (Deserts, ice, and clouds are lighter and reflect more sunlight than oceanic or forested areas.)

Glacial melt in Greenland (and elsewhere in the Arctic and Antarctic) also could increase methane release, spurring further warming. And as atmospheric methane increases Earth’s temperature, more water evaporates—but warmer air holds more moisture, which prevents heat from escaping into space. Then more glacial ice melts, reducing the surface albedo even more and releasing even more methane, and so on.

So we could have a foot of rise sooner than 2050?

Here’s where we’re at now: Sea levels are rising about 3 to 4 millimeters per year, with local variation. At some point, as we reach and surpass tipping points, sea level rise will speed up. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) states in its 2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report, “Failing to curb future emissions could cause an additional 1.5 - 5 feet (0.5 - 1.5 meters) of rise for a total of 3.5 - 7 feet (1.1 - 2.1 meters) by the end of this century.” Some models have an estimate for 2100 of about two feet if we significantly reduce emissions.

In the near- to mid-term, before we reach 2 degrees Celsius of warming, the most likely tipping points include collapse of Greenland’s and West Antarctica’s ice sheets, coral die-off, and Arctic permafrost thaws (which would release a lot of methane). (The original study in Science published in September 2022 is here.)

When will these tipping point events occur? We don’t know. Unfortunately, there’s no spreadsheet with specific dates listed. What we do know is that models have not always kept pace with warming in the past and may not fully account for all the interactions among feedbacks in Earth’s complex climate systems. So, for the sake of hypothesis, let’s say we might have more sea level rise than currently forecasted in the next decade, if only six inches or so.

That still doesn’t sound too bad. Superstorm Sandy had a surge of almost 14 feet.

Yeah, but the real problems are the global nature and ultimate inevitability of sea level rise. It will have massive human costs as well as massive financial costs. The last thing we need is for financial costs to make the human costs even worse and more widespread.

So, back to property insurance. Typically, insurance works because natural and manmade disasters don’t usually affect vast swaths of the property market at once. So the insurer makes money on all the collected premiums, collectively pays out less than that in reimbursement, and makes a profit.

But sea level rise will affect coastal properties worldwide. And there’s a critical, intangible tipping point that nobody talks about: the point at which low-lying coastal property is no longer insurable due to expected sea level rise, since more tangible tipping points are starting to be hit. Yes, it might take decades from the kick-in of the Greenland tipping point to realize many feet of sea level rise. But that doesn’t matter. What does matter is that when you can’t insure your coastal property anymore, and no one else can either, that’s a crisis—even if there’s only a foot of sea level rise. Or six inches. Or four. Whatever the point of no return turns out to be.

If every low-lying coast reaches that invisible tipping point around the same time, that could be a disaster for the insurance market—and for homeowners and businesses. A risk with 100% probability is not an insurable risk; it’s a guaranteed future loss for whoever insures it.

The clock is ticking, and the alarm is set, but we don’t know when it will go off.

You said something earlier about the structure of the insurance market?

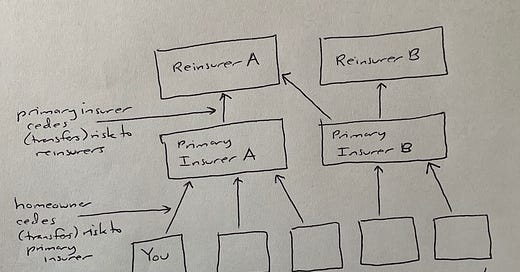

Right. Here’s how the insurance market works, in broad strokes:

You buy a property insurance policy from an insurer, but the insurer doesn’t necessarily hang on to all the risk in that contract. In many cases, the insurer sells (aka cedes) some risk to a reinsurer. A reinsurer is another insurance company, often in the specific business of reinsurance but sometimes also writing primary insurance, too. Reinsurers can be based in another state or even another country and may or may not have to post collateral.

The goal of reinsurance is that if a risk manifests (say, your property catches fire), the primary insurer—the company you pay premiums to—isn’t on the hook for all the losses, because the primary insurer also has insurance.

Fair enough. That situation might look something like this (note: this is a rough diagram; on a contracted project, you’d do weeks of stakeholder interviews to develop these!):

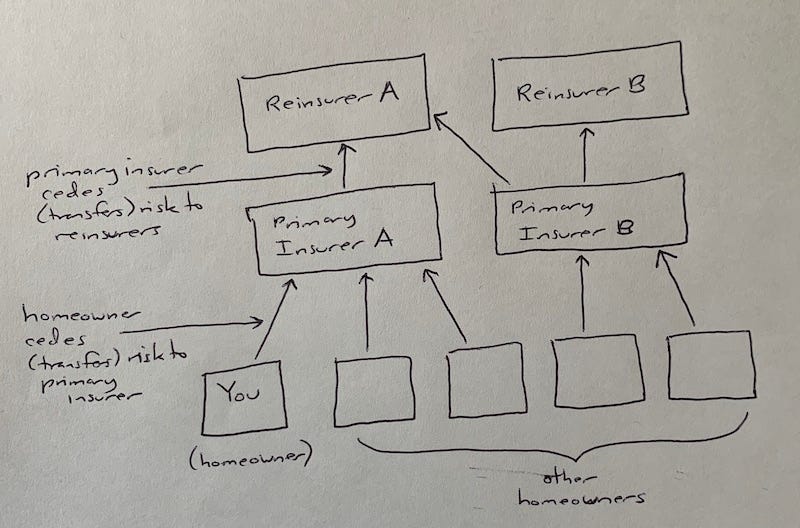

But this isn’t the full picture. Reinsurers also reinsure their risks. That practice is called retrocession. A reinsurer that takes on risk from the first reinsurer is called the retrocessionaire.

The say what now?

If you just head-banged against the table, yes. I feel you. But stay with me. As I was saying, a reinsurer can transfer (cede) risk to other reinsurers (retrocessionaires), which might be in the same or different jurisdictions. This process can occur many times, so it might look like this (again, this is just a rough diagram not based on interviews!):

Regarding the above diagram and the questions that might arise in your mind, Bank of Canada staff are on it. Please read this 2016 working paper that seems very relevant, as a start. (Really. Stop. Click that link. Then come back here later.)

There are also catastrophe bonds, which were introduced back in the 1990s and are now used by FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program, among others. This article is long enough, but you can read more about catastrophe bonds at Investopedia and in this Chicago Fed primer.

So, who own the ultimate risk if my house floods?

In normal times, it doesn’t matter. If you’re insured, your insurance company turns to its reinsurers (if any), the claim gets worked out, and you receive reimbursement. The primary insurer may take a loss on the portion of risk it did not reinsure, and some reinsurance company, somewhere, also takes a loss on the portion of risk that was reinsured.

The retrocession diagram earlier in this article might lead you to wonder if your primary insurer could end up reinsuring its own risks without knowing it. A well-known example of a reinsurance spiral is the 1980s Lloyd’s disaster, about which Institutional Investor wrote in 2007, “The reinsurance spiral was so complex and internecine that it turned out insurers were reinsuring their own reinsurers.” So, it’s technically possible, although it seems likely that practices have improved since the 1980s. (But read that Bank of Canada staff working paper if you didn’t before.)

Hmm. So, who owns the ultimate risk if tens of millions of houses flood?

That is a more complex question, but the answer is ultimately pretty simple: you might. You, the taxpayer. Not only because government-sponsored agencies often step in as the insurer of last resort, but because mega-disasters often require bailouts, as recent history has shown us (though the 2008 financial bailouts ultimately turned a profit for taxpayers).

And if you’re a homeowner in one of the flooded areas? You might get something, though the web of risk and liability could take a while to unwind. But, like I said before, your house might not actually flood before a trigger point is reached. The more likely scenario is that at some point your premium will go up, and up, and up, and then you simply won’t be able to get insurance, long before actual water starts lapping at the house foundations. What’s your plan for that scenario? Do you think you can see it coming and sell your house to someone else before the premium increases get too steep?

Is there any good news?

Yes. A difference from the 2008 financial crisis—and probably a good one—is that insurers typically renew flood insurance and reinsurance contracts annually and can reprice risk at that renewal. (Catastrophe bonds may have a longer lifespan.) These are opportunities for renegotiation and for gradual adjustment of risk premiums, which could incentivize homeowners to move away from risk zones over time—gradually.

The other good news, like I said, is that there is time—probably several years—before intangible tipping points hit. The bad news is that, given how far ahead of schedule climate change appears to be running, there’s probably less time than most people think.

What are the questions to be asking right now?

Here are some questions for insurers, reinsurers, and government agencies to ask themselves and each other:

What is the maximum amount of coastal flood risk I can comfortably shoulder?

How do I gain assurance that I have not exceeded that risk appetite?

How do we increase our certainty about model time estimates? Which models appear most accurate so far from a climate-change forecasting perspective, and how frequently are those models updated? How quickly can we act in response to model updates?

If a tipping point is reached and sea levels start rising faster, which coastal areas will be most and least impacted first?

Will there be sufficient warning to reprice risk as insurance and reinsurance contracts renew? If reinsurance contracts cannot be renewed, what are the next steps to handle potentially outsize risk in the near term?

What mechanisms are in place to trace risk through the insurance, reinsurance, and retrocession processes and ensure risk can be unwound cleanly in a large-scale event, including across international borders?

What additional mechanisms can be put in place in the next few years if the mechanisms currently in place to trace risk are not deemed sufficient?

How do catastrophe bonds increase and/or decrease systemic risk in various scenarios? How might the market for them evolve in the future?

What other firms are connected to insurers through the financial system?

How might federal and state governments offset excess risk if insurers step back? Will those steps be enough to sustain a housing market in coastal areas?

Should there continue to be a housing market in low-lying coastal areas, or should governments begin encouraging people to move before the sea rises?

How long until people start moving away from coastal areas on their own initiative due to skyrocketing insurance premiums, outright uninsurability, expense and futility of repeated flood repair and renovation, or loss of resale value?

What about people who refuse to leave? What responsibility, if any, does government have to ameliorate losses or help them relocate, if they bought the house when it was easily insurable?

Many of these are hard questions, but they’re worth exploring even if they can’t be fully answered right away.

What are the likely outcomes?

As climate change collides with people’s longtime affinity for coastal living, it will be a tough adjustment. In broad strokes, there are two possible outcomes (with many possible sub-permutations): a soft landing and a hard landing. Both involve significant pain for homeowners, insurers, reinsurers, and governments, but a soft landing could reduce systemic contagion risk by aiming to spread risks over time.

In a soft landing scenario, different coastal areas reach uninsurability at staggered times based on their idiosyncratic risk, with premiums first rising, then becoming difficult to get, then impossible, and with governments kicking in funds to help residents who bought property when climate-change risks were less of a known factor. Sort of an orderly, voluntary evacuation over time.

The goal would be to gradually reach a point at which, if someone wants to buy a flood-prone coastal property, they should be willing and able to self-insure that property. If they can’t afford to do that, maybe they shouldn’t buy it or should be willing to lose their entire investment.

Yes, that will hurt resale value of coastal real estate, but it’s better than everyone finding themselves in the lurch at once. That happened in 2008 when the real estate market crashed in many places simultaneously, and it was awful. Low-lying coastal real estate is doomed in the long run, yet people still seem enthusiastic about buying it. That mentality needs to shift in coming years and decades—and not all at once.

How about avoiding systemic risk contagion?

It’s vital to carefully track reinsurance of risk for coastal properties. If an insurer in Florida sells risk to a reinsurer in Switzerland, which then sells the risk to three other reinsurers in Germany and the US, which then sell the risk to two other reinsurers in the UK, that transactional trail should be clear and traceable, and total risk should not exceed any participant’s risk appetite.

That’s important because insurers don’t only write and reinsure property insurance. They write and reinsure disability insurance, life insurance, and long-term care insurance, among other lines of business. Regular people suffer if insurance companies go under. We learned that with AIG, which needed rescue in 2008 due to outsize derivative bets made by a single department within that company.

It was tough enough bailing out one huge insurance company. Can the world’s governments afford to bail out most of them and their reinsurers?

That’s a question I don’t want to see answered.

Me, neither. By recognizing the accelerating risk of coastal floods, and ensuring systems and processes are tracking risk across companies and countries and keeping it contained at manageable levels, companies, regulators, and governments can reduce financial risks. And if fewer people live on the coasts when the floods come because it’s already too hard to get flood insurance, fewer people will also die or lose their homes, and the toll of human misery can be mitigated, though not erased.

On the other hand, in a hard landing scenario, mostly nobody does anything until everyone has to do something all at once. That’s not a situation we want to be in if there’s any way to avoid it.

I finished my coffee ten minutes ago. What’s the takeaway?

The coasts will flood, probably sooner than models forecast. The timing is uncertain. And the intangible tipping point when insurance begins to become unaffordable will happen before that, also at an undetermined time, also likely sooner than expected.

But right now, there is time to take action and avoid a worst-case scenario.

-<>-<>-<>-

Further Links for Reading and Research

“Background on: Reinsurance.” Insurance Information Institute, November 24, 2020.

“Spotlight on: Flood insurance.” Insurance Information Institute, November 30, 2021.

“National Flood Insurance Program’s Reinsurance Program.” FEMA.gov

“Top 50+ Reinsurance Cases Every Risk Professional Should Know.” International Risk Management Institute, 2020. (Free IRMI account sign-up required)

“Insurer Insolvency and Reinsurance.” International Risk Management Institute, July 2004.

Oversight: NAIC Reinsurance Task Force, International Association of Insurance Supervisors, Federal Insurance Office.

Capital requirements for insurers in the EU (Solvency II) and in the US (Risk-Based Capital).

“The $5 trillion insurance industry faces a reckoning. Blame climate change.” - by Umair Irfan in Vox, October 15, 2021.

“Retrocession rates reflect nat cat pressure in insurance sector.” - by Robert Bissett at Lockton, February 8, 2022.

“Global Reinsurers Grapple With Climate Change Risks.” - by S&P Global Ratings, September 23, 2021.

“Reinsurance Challenged by Inflation and Climate Change.” - by Fitch Ratings, August 30, 2022.

“Rising sea levels put Miami, New York at biggest risk for severe and extreme flooding at commercial properties.” - by Joy Wiltermuth in MarketWatch, September 13, 2022.

This text was originally in the article but was interrupting the flow, so I moved it here so you can still read it: “For the rest of this article, we’ll walk through climate change model risk, under-appreciated tipping points, how the insurance market is structured, mitigating factors that could help insurers reduce risk over time as conditions change, and questions insurers and government agencies should ask now to prevent chaos and contagion later.

Fair warning: this might feel like a lot of information flying fast and furious.

I’m ready. Coffee is poured.

Great. Let’s dive into climate change.”

Wow this was a very great and timely read https://www.newsweek.com/florida-insurance-crisis-explained-1812418?amp=1 looks like some insurance companies are already cutting risk. Also thank you for including all of the further reading I can’t wait to dissect them! The link seems to be broken for ‘Top 50 reinsurance case studies every professional should know’ i was wondering if this was still available.