I was a huge fan of Universal Basic Income (UBI) when Andrew Yang proposed it in the 2020 presidential election cycle. He wasn’t the first person to come up with the idea, but he was the highest-profile US politician to seriously propose implementing it.

The idea is enticing. By paying each person a living wage, the theory goes, creatives will be freed to create art rather than grind away in The System, entrepreneurs will be freed to explore their innovative thought sparks, and everyone will have more time and flexibility to seek jobs that are good fits and to leave jobs that aren’t. All this redirection of energy will spark the economy to greater heights than it might have reached otherwise—or, at least, prevent people whose jobs get automated away from suffering and (perhaps eventually) rioting in the streets.

That’s the theory, in the broadest possible strokes.

But in the wake of the COVID pandemic, an interesting wrench gummed up the works: the U.S. tried a limited form of basic income called Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), which initially provided $600 a week to people who lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic, and later provided $300 a week after some tweaks.

The outcome: odds are high that it was a significant contributor to inflation.

Not so fast. What about the supply chains?

I’m not saying PFUC was the only contributor, or even the primary one. Pandemic supply chain shutdowns and backlogs were significant contributors, made worse by Russia’s attack on Ukraine, especially in the energy sector. Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans also may have played a role since they flowed to a wide range of companies with (usually) no repayment required. And household wealth increased sharply since 2019, boosting spending that can also drive inflation (it’s not all about wage income!).

But PFUC, for its part, did provide $2400 a month for a few months to millions of U.S. recipients, and later provided $1200 a month. That was quite generous, compared to the $3200 maximum.possible total of all-access pandemic stimulus checks per individual that people like to blame so much.

How many people received unemployment benefits, in general, during the pandemic period? The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that about 16% of U.S. residents age 18 and older applied for (edit: received) unemployment benefits between March 13, 2020, and December 21, 2020. That’s almost 40 million people. If we do an extremely rough ballpark calculation, using a Department of Labor estimate of $794 billion in combined federal and state unemployment benefits (not just PFUC) paid out between March 2020 and July 2021 (we assume people who started receiving benefits in December 2020 and earlier would collect unemployment for several months afterward), then:

$794,000,000,000 / 40,000,000 = $19,850 on average per person.

The real figure is likely somewhat lower, since additional people certainly applied for and received unemployment benefits between December 2020 and July 2021. Even if it were as low as $12,000 on average per person, that amount of money, multiplied by the millions of people who received it, could meaningfully contribute to inflation—especially since companies were broadly aware that millions of people were receiving that money, so companies could account for that information when making pricing decisions (aka raising prices).

That does not bode well for universal basic income.

Ugly math for a utopian idea

UBI, as traditionally envisioned, is typically proposed as a $1000-per-month payment to every person in a country. That’s also $12,000 per year. But there are about 335 million people in the U.S., so:

$12,000 * 335,000,000 = 4,020,000,000,000

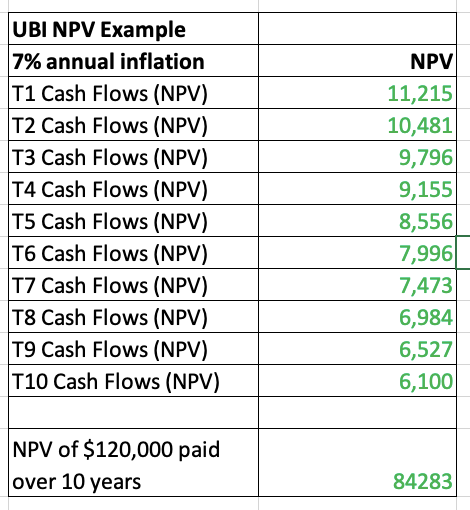

That’s $4 trillion per year. Um. I think inflation might possibly be a problem. And it could erode the benefits of implementing UBI in essentially just a few years. Here’s a time-value-of-money calculation of $12,000 annual UBI paid out over 10 years with 7 percent annual inflation1:

By year 10, half the value of the UBI is gone at 7% annual inflation. If inflation goes even higher, that number gets eroded even faster. And meanwhile, costs would likely be rising. People on fixed incomes who saw their rent skyrocket over the past few years understand how inflation can erode the value of a constant income.

I love the idea of UBI. I just don’t see how truly universal basic income could be effective in practice over the course of many years.

What are some ways around this?

One option might be to require community service as a condition of receiving UBI, maybe 10 hours per week. Recipients could choose how to fulfill the commitment based on their own skills and capabilities. That would reduce the absolute number of people choosing to claim UBI, which would reduce its potential contribution to inflation. A low-earning artist might still find that tradeoff worthwhile, as might someone who would otherwise work a minimum-wage job and now could do something more fulfilling with their time, but someone who could make more working their regular job might be unlikely to take the UBI if it meant an additional 10 hours per week.

Also, the community service performed would likely build capacity into the economy and help improve it overall, while also helping people in need.

Another, broader option beyond community service would be to pay people to do something, but of their own choice. It might be community service, artistic production, independent scholarship, research and writing, or entrepreneurship. But it ideally would involve, where possible, giving something back to keep the economy productive and simultaneously serve as a hurdle to reduce the number of beneficiaries and prevent inflation from spiraling out of control.

I want to believe in UBI. On the surface, it sounds like a simple and elegant solution to the likelihood that AI automation will make a lot of jobs obsolete. But it comes with significant tradeoffs, and I believe pandemic-era unemployment payouts provided a real-world, though limited, experiment showing us those tradeoffs. Policymakers should acknowledge that and seek ways to reduce the potential inflationary impact before making UBI the law of any land.

Yes, I know inflation isn’t constant across years. The point is, it would likely be relatively high if UBI were suddenly implemented. The time-value-of-money formula used here is: 12000 / 1.07 + 12000 / (1.07)^2 + 12000 / (1.07)^3 + 12000 / (1.07)^4 + 12000 / (1.07)^5 and so on

Great writing and informative. Societies make big bets when faced with unusual circumstances. There are a number of very large bets that were made during the pandemic. It will be useful to see which ones pay off and which ones look back in the years to come. Putting all your chips on red on the roulette table is a rush. Big risk though.

Yours is my favorite Substack that is willing to ask readers to understand the implications of NPV :)

I tend to believe the unwinding of the supply chain and the emergence of the means to effiiciently target disease on the fly will be the big bets that change our world for the long-term. Since we've been experiencing Corona-configured viruses for decades now, I figure we will be readier next time around DESPITE government programs like PPP and FPUC.

The revisions to the supply chain are in progress. The winners and losers are an interesting bet to see play out. Apple was the most aggressive of all firms on Earth in betting on totalitarianism in China as a way to make cool stuff. I think analysts believe it will take them 15 years to unwind from being full partners with the PRC. Diversification of the supply chain will provide resiliency. Their #1 priority remains not becoming associated with totalitarianism in the meantime. I suppose Tesla's tight integration with the PRC is a similar big bet.

The COVID-19 dress rehearsal left about 25% of the world unvaccinated. A new virus that is better at killing us will test our world resolve in caring about humanity much more. I hope we do better next time.

An interesting article. It just goes to show how complicated an idea for the 'good' of people can be. To the extent it could become a constraint or even a millstone in future scenarios.

But then your piece here demonstrates the virtue of raising ideas for public scrutiny. Once out in the open, they give the opportunity for more thought, more ideas, good and bad, reasoned debate, and balanced argument. It seems, to me at least, innovation comes from open exploration, conversation, 'have you considered this' debates. Far better than later conspiracy or forsaking the future because of past misgivings.

A problem in my mind, which I am convinced was been had multiple times in the 18th, 19th, 20th, and now 21st century, if we make money by stripping away the jobs of 'working people' where will money come from to expand the economy? Or does it even matter, if a few can get massively rich today? Ahhh, yes, the later is the more pertinent issue for today's economies around the globe. Isn't it? But then this surely begs a question about the validity and long-term viability of current thinking on GDP, Tax, payment of the workforce, share capital, etc etc, etc.

Yes, an interesting yet incredibly complex and profound subject matter, again, very well articulated.