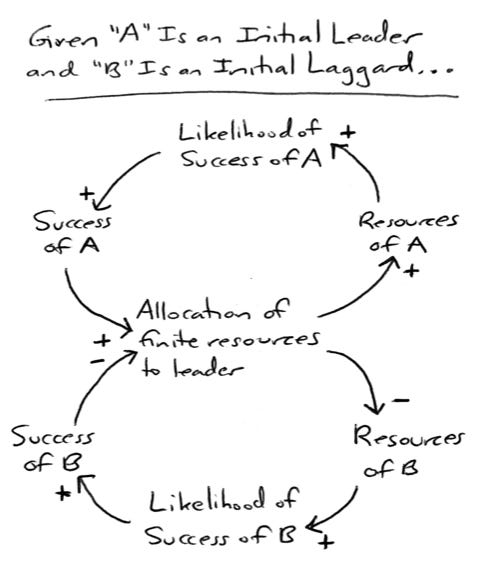

The field of system dynamics identifies several archetypes: common patterns that drive behavior in many situations. One of the most salient archetypes of our current period is called “success to the successful,” which fairly well describes twenty-first-century capitalism or the late stages of the board game Monopoly. It looks like this:

(Note: for a primer on reading and drawing causal loop diagrams, you can read my essay on that topic.)

In this diagram, as A succeeds, A receives more resources from a (presumed) finite pool of resources1, so B therefore receives less. As resources available to A increase, A’s likelihood of success2 also increases, and as A’s success increases, A receives even more allocation of resources. Meanwhile, as resources allocated to B decrease (which happens because resources allocated to the leader A increase), B’s overall resources (relative to A) decrease, B’s likelihood of success tends to decrease, and as B’s likelihood of success decreases, resources allocated to B (relative to A) also tend to decline further.

A Poker Example

The diagram above shows just two entities, and a good two-entity example is to think of the final two players in a poker tournament: eventually, after some variable number of hands, one player will be left with nothing, and one player will have all the chips and win the tournament.

But a poker tournament might start with 100 or 1000 or 10000 players, and eventually there is a final table of nine players. Those nine players might keep playing, allowing the dynamic to proceed to its logical conclusion of a single winner—or, if they’re a more cooperative group and if tournament rules allow, they may choose to split the prize pot so that each member of this top tier will walk away with some winnings.

A Markets Example

To generalize a bit about the “success to the successful” archetype as it manifests in messy real life, it may help to think of the two entities in the diagram as “the top tier versus everyone else.”

Let’s make this concrete and relevant to early 2023: we’ll say A represents a group of companies known as MMANGA (Microsoft, Meta, Apple, Nvidia, Google/Alphabet, Amazon), and B represents a group of all other companies in the US public markets (i.e., a broad-based index minus MMANGA).

Since 2010, with only relatively short breaks, the success-to-the-successful loop has been operating for MMANGA companies, which have become behemoths via organic growth as well as acquisitions and investments. And now, because of legitimate AI innovation and accompanying hype, Group A is once again in the top tier of stock-market performance in 2023 (so far), compared with Group B.

As Group A succeeds, their success tends to increase the likelihood that investors will allocate funds to Group A (to the extent they expect future outperformance) rather than to Group B. (There are also counterincentives, which make markets interesting: Group A’s high performance means significant gains have already been captured, and these companies have large market caps, so it’s unclear how long Group A can outperform at its current pace.3 The success-to-the-successful dynamic may shift soon if growth saturation and/or disruptive shock occurs, or it may continue for quite a while. There are no guarantees in risk!)

A Life-Opportunities Example

Let’s look at another example: performance of students identified as gifted at an early age4. If Student A is identified as gifted in third grade, and Student B is identified as average in third grade, what happens? Let’s look at our diagram again:

According to the “success to the successful” archetype, a school that identifies Student A as “gifted” is more likely to allocate resources to Student A (say, a gifted-and-talented teacher, extra classes or field trips, and connections to mentors). Student A and Student B both benefit from regular school resources, but only Student A also benefits from gifted-and-talented resources.5

As time goes by, the increased resources provided to Student A further increase the likelihood of Student A’s success, and if Student A in fact becomes more successful6, even more resources (e.g., scholarships, summer courses, grants) will probably become available to Student A. Student A will likely attend a top university, where they will have access to access to job interviews with top companies that visit the campus.

Meanwhile, Student B’s likelihood of success does not receive a boost via additional resources starting in third grade, so relative to Student A, Student B’s performance lags more than it would have if they had equal resources.7 If Student B eventually attends a good-but-not-great college, the companies that Student A interviewed with may not even come to Student B’s campus. That’s, unfortunately, a success-to-the-successful loop in action. (It’s definitely possible to break out of this loop if you’re Student B, but it takes significant effort. Going to grad school is one way. Starting a company is another. Working your way up in a corporation is another.)

How Success-to-the-Successful Can End

In real life, forever-upward trajectories with no interruptions are vanishingly rare, and success-to-the-successful loops rarely continue forever. “Into each life some rain must fall,” as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote in his poem “The Rainy Day.” Our gifted student, after acing college and getting their first hotshot job, may continue upward or hit some roadblocks. Maybe they struggle to shift from academic performance to on-the-job collaborative achievement. Maybe they have a health issue. Maybe they get promoted to a role that maxes out their current capabilities and then struggle to advance beyond it. Either way, it looks like their performance is saturating, just like the famous growth S-curve:

But that’s not destiny. A saturating S-curve can be viewed, in zoom-out, as a plateau on which to consolidate resources before another leap upward on a different path. Or, it may turn out to be a peak before a downward slide. Or, it could be one of several breath-catching pauses on a relatively continuous trajectory. It depends on the individual and the circumstances and can’t necessarily be predicted in advance.

Archetypes aren’t destiny. But knowledge of them can help us identify potential ruts and opportunities—and guide our decisions as we steer and shape our own paths.

Extra, Extra!

For curious readers:

Systems Archetypes I - by Daniel Kim - covers this and many more system dynamics archetypes in detail.

The Systems Thinker - large collection of systems thinking resources and articles.

If there were infinite resources freely available, this archetype likely would not describe the situation.

The traditional diagram for this archetype shows just “success” and leaves out “likelihood of success,” but history shows that just because an entity has a lot of resources, that doesn’t necessarily mean it will be successful. Kodak is an example. There’s a tendency to be successful given more resources, but it’s not a guarantee.

A full system dynamics diagram for year-to-date market performance would not simply consist of a success-to-the-successful loop; it would also include various countervailing forces.

I’m a proponent of G&T programs, but it’s important to acknowledge that they do produce “success to the successful” loops—and to ensure extra resources aren’t extended only to book-smart students. Schools should help every student find the area(s) where they most excel. Public schools are not good at this in their present incarnation.

Special-education students also benefit from additional resources, but those resources are meant to serve as a balancing loop, helping students who face challenges to meet academic standards and gain life skills.

Remember, likelihood of success does not guarantee actual success!

Student B does have opportunities to identify their own strengths, but that’s largely left to Student B to do independently in our current system. There aren’t many “gifted” programs for electricians or salespeople, for example, even though those are totally viable careers. We under-define “gifted and talented”—the term can encompass many more skills than schools currently recognize.

Hi Stephanie - I love your casual loop diagrams.

Seems to me there are two assumptions in this logic - both A and B need the same types of resources and both utilize them at the same efficiency. So if one is getting fewer resources, they are producing less output; which means they will get fewer resources, and the loop continues. This works if resources are controlled by those who expect a return, which is then tied to output.

Most importantly your article highlights how we can break out of this cycle by innovating and jumping to a new S curve.

While not exactly on point, system design often creates the distortions that predict outcomes. Many years ago I read a book by Malcolm Gladwell. It focused on a couple of youth sports activities, as I remember Little League baseball and hockey. Both of these sports had STRICT rules on age eligibility and dates when a kid turned 6 for example. It turns out, in both cases, that the very best and exclusive teams at age 18 will be LOADED with kids who were 5 years, 11 months in age since those children will SIMPLY be nearly 17% more mature than their peers. If I remember correctly the Olympic Gold Medal team for ice hockey had more than 70% of the players born in the most advantageous month. Perhaps parents interested in sports should plan their births accordingly :) Those kids get on the "better" team from the start and often stay together through youth. This is the danger of G&T programs as they are arbitrary in selection of aptitude at a given time. This has consequences and is best exemplified in nations with high--stakes aptitude testing.